It appears that a man sporting the latest trend in beards is doing it for more than just form – there’s a lot of function behind it too.

A 2020 study by a trio of University of Utah researchers, including mechanical engineering assistant professor Steven Naleway, shows that a beard can provide some extra form of protection from a punch in the face. That unusual finding earned Naleway (pictured, center), along with U biological sciences professor David Carrier (pictured, left) and recent biology graduate Ethan Beseris (pictured, right), the 2021 Ig Nobel Prize.

A 2020 study by a trio of University of Utah researchers, including mechanical engineering assistant professor Steven Naleway, shows that a beard can provide some extra form of protection from a punch in the face. That unusual finding earned Naleway (pictured, center), along with U biological sciences professor David Carrier (pictured, left) and recent biology graduate Ethan Beseris (pictured, right), the 2021 Ig Nobel Prize.

Let’s not confuse it with the Nobel Prize, that well-known top prize for achievements in science. The trio took home the much less-lauded Ig Nobel Prize, a humorous award intended to celebrate scientific accomplishments that “first make people laugh, and then make them think.” The U study is among this year’s 10 awardees, and it is the first time the U has won the prize.

The lighthearted awards, presented by Marc Abrahams of the science humor magazine Annals of Improbable Research, are a counterpoint to the mainstream Nobel Prizes, which will be awarded in October.

“I honestly think it’s pretty cool that we got selected as Ig Nobel Prize laureates,” says Naleway. “I am a big believer in the fact that there’s a lot of value to research that’s approachable for people.”

The study, published in April 2020 in Integrative Organismal Biology, continues a line of research that Carrier has been pursuing for years. Given that humans are the only primates who fight by punching, could there be other aspects of human anatomy that evolved in connection with fisticuffs?

That question is called the “pugilism hypothesis,” and Carrier has explored how different features unique to us among primates (planted heels, proportions of face bones, ability to form a fist and upper arm strength in males) specialize humans, particularly males, for fighting by punching.

“And so the beard, which our study shows provides some protection to some of the most vulnerable parts of the face when people punch, is just one more piece of the series,” says Carrier, who himself sports a nicely coifed set of facial hairs.

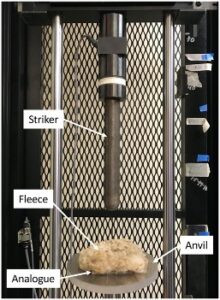

The researchers covered a fiber epoxy composite material similar to bone with sheep fleece, an analog for facial hair. They then dropped different weights onto the samples and found that samples with fleece absorbed 37% more energy than hairless samples and could withstand 16% more force before breaking.

Naleway’s involvement stems from his research in biomechanics and materials science. “If you talk to the researchers who do this kind of work, some of that biomechanics component is kind of missing,” he says, “and it can help us understand what’s going on, which obviously for this application of protection is incredibly important.”

Why does this matter from an evolutionary perspective?

“The beard covers the mandible, which is one of the primary targets,” Carrier says. “And when it breaks, without an orthopedic surgeon you’re in big trouble. If you broke a jaw 5,000 years ago, that was a life-threatening injury.”

This year, the awards ceremony includes presentations of awards by “genuinely bemused genuine” Nobel laureates, an original mini-opera, very brief lectures on topics from drinking coffee to baby-washing technology and, according to the ceremony website, lots of paper airplanes.

Read more about past awards here.