For today’s electrical engineering students at the John and Marcia Price College of Engineering, there’s nothing strange about the idea of invisible charged particles instantaneously traveling thousands of miles through a bit of stretched out metal; it’s a fundamental fact of their discipline.

But for Hakon H. Haglund, who graduated from the U with a degree in electrical engineering in 1921, this was a relatively new concept. Born in Larvik, Norway in 1889, Haglund entered a world where Edison’s incandescent lightbulb was less than a decade old and the first national electricity utilities were in the process of being built.

Growing up alongside electrification itself had a profound impact on Haglund, influencing a journey that would both take him around the world and solidify Salt Lake City and the University of Utah as his home. It would also be the start of a legacy: three generations of Haglund alumni and a scholarship that bears his name.

The Hakon and Eva Haglund Scholarship, in memory of a proud alumnus and his partner, seeks to enable others to overcome unforeseen hurdles and complete their engineering education.

Hakon Haglund’s own circuitous path into the nascent field of electrical engineering had its own challenges and unforeseen hurdles. After the death of his father when Haglund was only three, his mother moved him and his brothers first to Sweden, then to America a decade later, eventually settling in Salt Lake City.

Learning English as quickly as he could, Haglund’s first foray into the world of electrical engineering was at 17, when he worked as a licensed electrician for the Salt Lake Electric Supply Company, Intermountain Electric Company, and Borkman Electric Company. And though he excelled in these booming trades in his newly adopted home, it was not until he traveled halfway around the world — again — before he started formally studying the discipline.

While on a religious mission in Hawaii, Haglund began taking correspondence courses in electrical engineering, and soon found ways to apply his interest. One of his companions on the mission, Elder Castle H. Murphy, wrote that Haglund was able to diagnose a burnt-out armature at a local sugar mill by smell alone, and was able to repair it himself, rather than sending the mechanism back to San Francisco.

While in Hawaii, Haglund had also been corresponding with another member of the Swedish community in Salt Lake City, Eva Forsberg. Haglund returned to Salt Lake City in 1911, taking a job with Western Union Telegraph as printing technician, and the two would marry a year later.

Despite the economic pressures of raising a young family, and in an era where scholarships and other financial support was non-existent, it was Eva who encouraged Haglund to pursue a degree in electrical engineering from the University of Utah.

Haglund enrolled in 1914 and studied while maintaining his position at Western Union. While it was a taxing load for a new father — Hakon and Eva’s first daughter was born that year — working at the intersection between the commercial and academic worlds was a key factor in his career trajectory. Haglund taught Morse Code, a critical skill during the early years of World War I, and would later develop new techniques for maintaining Western Union’s type-wheels.

Proving invaluable to the telegraph company’s management, and with the support of Joseph Merrill, Director of the Engineering School, Haglund transferred to Western Union’s Engineering Department in New York after graduating in 1921, family in tow. This would be a start of another globe-spanning adventure, as Haglund’s engineering expertise had expanded into the development of new undersea transmission cables, and he was later dispatched to the Azores to direct the installation and testing of the designs he and his colleagues had produced in conjunction with Bell Labs.

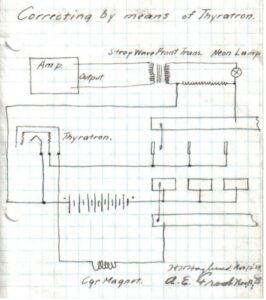

After a year in the Portuguese islands — a term artificially extended by an earthquake — Haglund’s focus turned to developing new technologies, as well as the next generation of electrical engineers. He was active in the design and application of new printers, signal-shaping amplifiers, and repeaters, but also in the process of documenting these new findings and those of his colleagues. Haglund was named to Western Union Committee on Technical Publication, ensuring that others could build upon their work.

And though Hakon “Happy” Haglund died in 1960, his legacy continues to impact generations to come as descendants of him and Eva established a fund to provide student’s financial aid for books in the early 1970’s. Their grandchildren — led by Howard Jr., Paul (BA Math ‘78), and Christine Seppi have followed suit in recent years by funding a series of annual scholarships for engineering students in danger of dropping out due to financial hardships. Showing further commitment the descendants of Hakon and Eva Haglund have committed to building an endowed scholarship program that will provide support to engineering students in need perpetually — with an eye to inspiring engineers who have the same drive Hakon had.