Humans have been working with glass for thousands of years. But what happens when this ancient practice meets the manufacturing techniques of the 21st century?

Additive manufacturing, more commonly known as 3D printing, is a collection of related technologies that can work with an ever expanding range of materials. Glass, however, remains elusive due to its relatively high melting temperature and disordered internal structure. Existing glass printers are mostly suited to large, decorative objects and not the ultra-precise applications scientists and engineers have in mind.

That’s the motivation behind a new National Science Foundation project known as STELLAR: Scalable low temperature ultrafast laser materials manufacturing. Led by researchers in the University of Utah’s John and Marcia Price College of Engineering, the project aims to develop a glass-based 3D printing system capable of manufacturing features as small as 1 micrometer over centimeter areas, which is beyond what is attainable with current technologies.

The $1.4 million Award is split between the University of Utah, University of Galway in Ireland and Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland.

The project leaders, Berardi Sensale-Rodriguez and Rajesh Menon, are both professors in Price Engineering’s Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering. Glass has a number of critical mechanical properties, but as electrical engineers, it’s glass’ optical properties that are most interesting.

“If we can shape glass on a microstructural level, we can gain new levels of control over light across different wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum,” says Menon. “That could lead to applications like sensors or nanosatellite telescope lenses.”

If researchers want to make these sorts of precise glass components now, they use “top down” techniques, starting with a block or sheet of glass and etching it away until the desired shape is reached. Additive manufacturing’s “bottom up” represents new possibilities.

“A bottom-up approach can enable more flexibility of the shapes that can be made, compared to what could be done by etching the material from the top down,” says Sensale-Rodriguez.

A typical 3D printer works by melting plastic and extruding it in layers, gradually building up the desired shape as those layers cool and harden. More advanced printers can work with tougher materials that have much higher melting temperatures, such as steel or titanium, but use an entirely different way of building up the material. Those printers start with a bed of metal powder, then use powerful lasers to instantly fuse it solid at the desired points.

The U researchers propose to use a similar approach with glass. Their innovation is increasing the speed and accuracy of the laser involved. Current state-of-the-art glass printers melt thin glass filaments with conventional lasers and have poor resolution; they can only produce objects with relatively large features. The STELLAR project’s system will employ ultrafast lasers to achieve the precision necessary for microscopic applications.

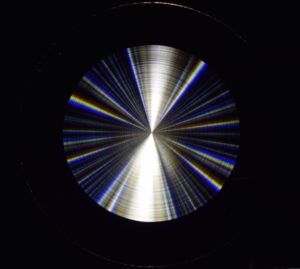

“Femtosecond lasers turn on and off in a millionth of a billionth of a second, says Menon. “Combined with advanced beam shaping and our computational modeling approach, this system will give us unprecedented control while using 80% of the energy of traditional methods.”

The researchers will test their system by printing a glass planar resonance sensor. These devices work like a mechanical eardrum, “hearing” reflected microwaves and providing information about whatever they bounced off of. The submicroscopic wavelengths involved mean these sensors can detect the presence of specific chemicals, microorganisms, or surface structures all depending on how they’re shaped.

“This kind of sensor can actually test the mechanical properties of the glass itself,” says Sensale-Rodriguez. “So we are taking advantage of the printing of the material as a way to test the properties of the material simultaneously.”

In addition to supporting the research that will go into developing the STELLAR system, the NSF grant will support an exchange program between students from the U and those from University of Galway and Queen’s University Belfast.