Electronic waste, or e-waste, is a rapidly growing global problem, and it’s expected to worsen with the production of new kinds of flexible electronics for robotics, wearable devices, health monitors, and other new applications, including single-use devices.

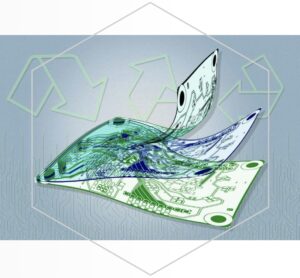

A new kind of flexible substrate material developed at MIT, the University of Utah, and Meta has the potential to enable not only the recycling of materials and components at the end of a device’s useful life, but also the scalable manufacture of more complex multilayered circuits than existing substrates provide.

The development of this new material is described this week in the journal RSC: Applied Polymers, in a paper by MIT Professor Thomas J. Wallin, University of Utah Price College of Engineering Professor Chen Wang, and seven others.

“We recognize that electronic waste is an ongoing global crisis that’s only going to get worse as we continue to build more devices for the internet of things, and as the rest of the world develops,” says Wallin, an assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering. To date, much academic research on this front has aimed at developing alternatives to conventional substrates for flexible electronics, which primarily use a polymer called Kapton, a trade name for polyimide.

Most such research has focused on entirely different polymer materials, but “that really ignores the commercial side of it, as to why people chose the materials they did to begin with,” Wallin says. Kapton has many advantages, including excellent thermal and insulating properties and ready availability of source materials.

The polyimide business is projected to be a $4 billion global market by 2030. “It’s everywhere, in every electronic device basically,” including parts such as the flexible cables that interconnect different components inside your cellphone or laptop, says Wang, assistant professor in Price Engineering’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering. It’s also widely used in aerospace applications because of its high heat tolerance. “It’s a classic material, but it has not been updated for three or four decades,” he says.

However, it’s also virtually impossible to melt or dissolve Kapton, so it can’t be reprocessed. The same properties also make it harder to manufacture the circuits into advanced architectures, such as multilayered electronics. The traditional way of making Kapton involves heating the material to anywhere from 200 to 300 degrees Celsius. “It’s a rather slow process. It takes hours,” Wang says.

Continue reading David L. Chandler’s “New Substrate Material for Flexible Electronics Could Help Combat e-Waste” at MIT News.