U Researchers Create First Flat Telescope Lens that Can Capture Color

For centuries, lenses have worked the same way: curved glass or plastic bending light to bring images into focus. But traditional lenses have a major drawback—the more powerful they need to be, the bulkier and heavier they get. Scientists have long searched for a way to reduce the weight of lenses without sacrificing functionality. And while some slimmer alternatives exist, they tend to be limited in their capacity and are generally challenging and expensive to make.

Now, new research from Price Engineering professor Rajesh Menon and colleagues offers a promising solution applicable to telescopes and astrophotography: a large aperture flat lens that focuses light as effectively as traditional curved lenses while preserving accurate color. This technology could transform astrophotography imaging systems, especially in applications where space is at a premium, such as on aircraft, satellites, and space-based telescopes

Their latest study was featured on the cover of the journal Applied Physics Letters and was led by Menon lab member and ECE Research Assistant Professor Apratim Majumder. Their coauthors include fellow Menon lab members Alexander Ingold and Monjurul Meem, Department of Physics and Astronomy’s Tanner Obray and Paul Ricketts, and Oblate Optics’ Nicole Brimhall.

If you’ve ever used a magnifying glass, you know that lenses bend light to make objects appear larger. The thicker and heavier the lens, the more it bends the light, and the stronger the magnification. For everyday cameras and backyard telescopes, lens thickness isn’t a huge problem. But when telescopes must focus light from galaxies millions of light-years away, bulky lenses become impractical. That’s why observatory and space-based telescopes rely on massive, curved mirrors instead to achieve the same light-bending effect, since they can be made much thinner and lighter than lenses.

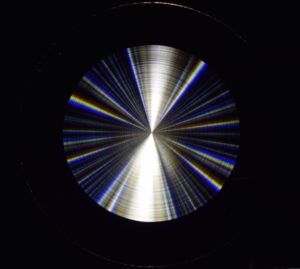

Scientists have also tried to solve the bulkiness problem by designing flat lenses, which manipulate light in a different way. One existing type, called a Fresnel zone plate (FZP), uses concentric ridges to focus light, rather than a thick, curved surface. While this method does create a lightweight and compact lens, it comes with a tradeoff: it can’t produce true colors. Rather than bending all of the wavelengths of visible light at the same angle, the ridges of a FZP diffract them at different angles, resulting in an image with chromatic aberrations, or color distortions.

Enter Rajesh Menon and his team at the U. Their new flat lens offers the same light-bending power as traditional curved lenses while avoiding the color distortions of FZPs.

“Our computational techniques suggested we could design multi-level diffractive flat lenses with large apertures that could focus light across the visible spectrum and we have the resources in the Utah Nanofab to actually make them,” says Menon.

The key innovation lies in the microscopically small concentric rings that the researchers can pattern on substrate. Unlike the ridges of FZPs, which are optimized for a single wavelength, the size and spacing of the flat lens’ indentations keep the diffracted wavelengths of light close enough together to produce a full-color, in-focus image.

“Simulating the performance of these lenses over a very large bandwidth, from visible to near-IR, involved solving complex computational problems involving very large datasets,” says Majumder. “Once we optimized the design of the lens’ microstructures, the manufacturing process involved required very stringent process control and environmental stability.”

A large, flat, color-accurate lens could have massive implications across industries, but their most immediate application is in astronomy. The researchers demonstrated the capabilities of their flat lens with test images of the sun and moon.

“Our demonstration is a steppingstone towards creating very large aperture lightweight flat lenses with the capability of capturing full-color images for use in air-and-space based telescopes,” says Majumder.

This work was supported by DARPA (FA8650-20-C-7020 P00001), the Office of Naval Research (N00014-22-1-2014), and NASA (NNL16AA05C). This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these funding agencies. Monjurul Meem is now a process engineer at Intel.